Once considered useless swampland by European settlers, wetlands are now recognized as nature’s multi-purpose ecosystems. They recharge groundwater, store floodwaters and snowmelt, clean up pollution and serve as habitat for a wide variety of plant and animal species. If that weren’t enough, wetlands also store carbon within their plants and soil which means they play an important role in climate change mitigation.

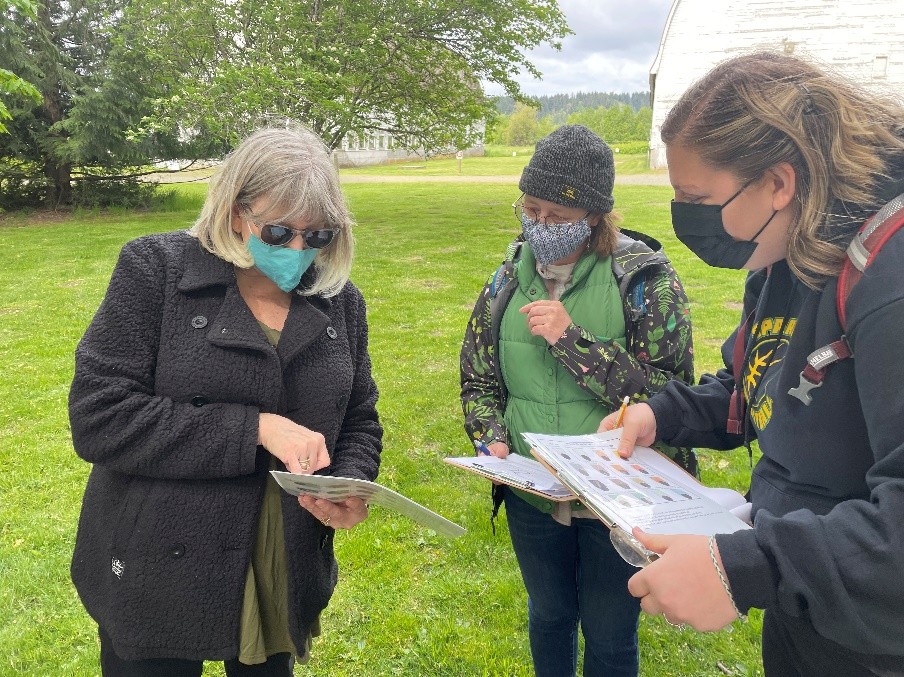

In May 2021, twenty-nine educators from eight school districts along with outreach coordinators from community-based organizations explored how wetlands are a solution to climate change through a pilot climate science workshop delivered by the Pacific Education Institute (PEI) as part of OSPI’s ClimeTime project work. The purpose was to provide teachers with tools for integrating wetlands-focused, culturally responsive climate science into their curriculum with K-12 students.

Participants learned about the historical and cultural connections to local wetlands by hearing from Nisqually Tribal Council Member Hanford McCloud, a PEI board member. The workshop was held over three sessions, with an in-person visit to the Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge between two virtual courses over eight days. During the initial virtual portion, participants learned about the role of wetlands in mitigating climate change and heard from McCloud about how the tribe and the Refuge work together to ensure the ongoing health of this critical ecosystem.

McCloud, a master weaver and a member of the team that developed the statewide Since Time Immemorial curriculum, also spoke about the role of cedar trees in both wetlands and Tribal life. “The unique thing about cedar trees is that in spring, there’s no sap in the bark,” he explains. “It’s like somebody turns them on and the sap disappears, so you can peel the outer bark and get this roll of pliable fiber and make whatever you want out of it.”

At the refuge, teachers participated in hands-on activities and learned about regional history from a Tribal perspective. McCloud explained the importance of the Medicine Creek Treaty and shared the ecosystem changes he has noticed over time.

Hattie Osborne was PEI’s South Sound FieldSTEM coordinator at the time. “The teachers learned so much from Hanford’s presentation,” says Osborne. “He talked about his relationship with the land and the history of the northern part of Thurston County that is now Yelm and Lacey. People asked me for his contact information so they could send him a personal thank you.”

For McCloud, sharing knowledge is a continuation of a tradition he learned from generations within his family. “I want to make an impact,” he says. “When my ancestors, my Uncle Billy [Frank] and Grandma Janet McCloud, walked this path it was pretty bumpy and had a lot of potholes. Now they’ve paved these paths by working and fighting hard. It’s our turn to make sure we maintain that continuity and give information to one another. I want to give the teachers these tools and this information and an outlet to say, ‘Who can I call?’

Many of those who attended are interested in bringing McCloud to their classrooms or introducing him as a resource to fellow teachers. “They felt like they had a connection to Hanford, and he wanted them to feel comfortable enough to reach out to him,” says Osborne. “He definitely accomplished that. We had one librarian in the group, and she decided she wants to make an effort to incorporate Indigenous authors and local stories into the time she has with the students.”

The Solutions Oriented Learning Storyline Wetlands workshop is one of a series of climate science professional learning opportunities for K-12 teachers that take a solutions-oriented approach to climate change through explorations of topics like forest carbon sequestration, regenerative agriculture, erosion and food waste. At the workshops, educators see how Solutions Oriented Learning Storylines integrate climate science with English Language Arts (ELA), civic education and the Since Time Immemorial Tribal sovereignty curriculum.

During the final virtual session, PEI Bilingual Environmental Faculty Lourdes Flores Skydancer shared best practices for using the Storyline with English Language Learners (ELL) and Nisqually River Foundation Education Project Program Director Sheila Wilson and South Sound G.R.E.E.N Project Manager Stephanie Bishop provided wetland resources to use with students.

The following year, an additional 29 educators from 15 school districts attended a second coastal wetlands workshop held in person at the Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge. Teachers participated in hands-on activities and learned about regional history from a Nisqually perspective. Nisqually Tribe Education Liaison to the State Board of Education (SBE) Bill Kallappa hosted a guided walking tour of the refuge, focusing on Tribal management of wetland-related natural resources and climate change planning shared about the Nisqually Tribe’s connection to the Nisqually watershed and role as a partner and leader in helping return the Nisqually estuary to its natural condition.

“[I’ll be] sharing the middle and high school storyline with my district wide Professional Learning Communities,” said one participant. I loved the indigenous focus – I’m looking to include more of this.”