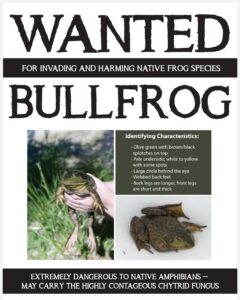

In August 2020, a group of teachers attending one of PEI’s Washington Invasive Species Council (WISC) workshops learned about invasive American bullfrogs from a knowledgeable guest presenter with a strong background in the subject. After sharing ways to identify the non-native frogs and details about how they kill native frog species either deliberately by eating them or inadvertently by spreading disease, he fielded questions from the audience.

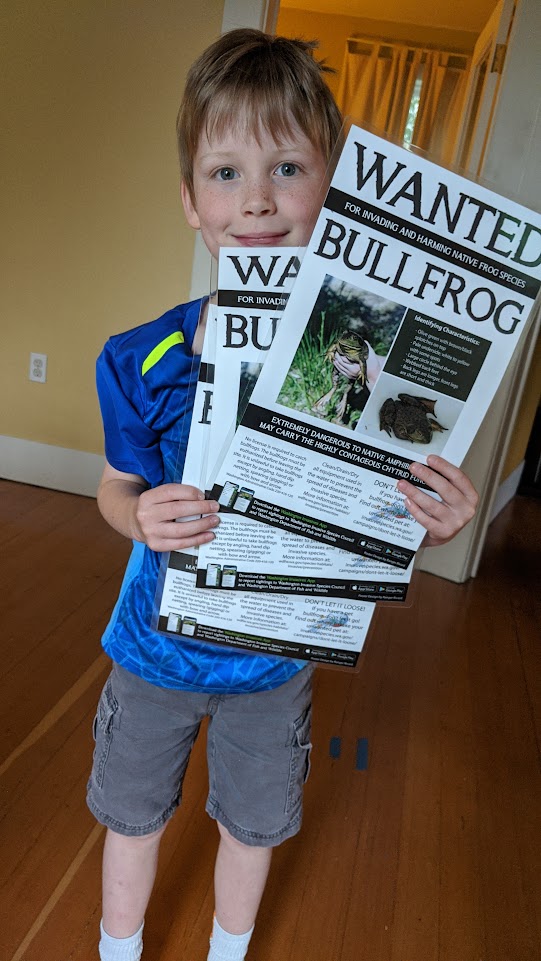

The speaker was not a biologist or game warden with the Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife, but Ranger Rivard, the eight-year-old son of PEI’s Central Washington FieldSTEM Coordinator Megan Rivard.

What he dubbed ‘Ranger’s Bullfrog Project’ demonstrated to the teachers just how engaged students of all ages can become when they learn about invasive species. For WISC, the project also provided valuable data.

“When we pull up the map, it looks like there are not bullfrogs in Eastern Washington,” says WISC Executive Coordinator Justin Bush. “From a policy and program-building perspective, if we don’t have that data, we can’t build policies or ask for funding to address it. Ranger was educating his friends to go into local ponds and document bullfrog populations and then humanely euthanize them. The kind of information he provided is very useful.” Bush provided advice and feedback for Ranger’s project.

PEI and WISC have been collaborating since 2015 to develop curriculum and workshops that introduce educators to the many ways invasive species can be integrated into lessons. The partnership benefits both organizations, according to Bush and PEI Program Director Denise Buck. For WISC, training teachers to educate their students about invasive species multiplies the number of people on the lookout for non-native plants, insects and animals. In the last 30 years, more than 90 varieties of insects alone have been found in Washington State for the first time.

“A lot of our focus is on prevention and finding new species and then taking our limited resources to get rid of them fully. To do so, we need more eyes and more trained experts. Creating a curriculum and having teachers implement it is the key to creating the next generation of biologists, entomologists and species managers.”

— Justin Bush, Washington Invasive Species Council Executive Director

“More than half of those first detections were made by what we would call citizen scientists,” Bush explains. “A lot of our focus is on prevention and finding new species and then taking our limited resources to get rid of them fully. To do so, we need more eyes and more trained experts. Creating a curriculum and having teachers implement it is the key to creating the next generation of biologists, entomologists and species managers.”

WISC Community Outreach and Environmental Education Specialist Maria Marlin is in the process of adapting the middle school curriculum developed with PEI for use by informal educators such as nonprofit groups or environmental education centers. “It’s not realistic for Maria to go to every Boy Scout chapter and Y.M.C.A. camp to lead these trainings, so we need to create partnerships in order to deploy those resources,” says Bush. “Our work with PEI and formal educators has inspired us to look at how we can apply this model to informal educators as well.”

For PEI’s part, invasive species are a relevant topic that easily engages both educators and students. “We love partnering with experts like WISC,” says

Program Director Denise Buck. “We all know invasive species are out there but we’re not totally clear about them. When we see evaluations from teachers, they appreciate knowing more about the topic and they understand the value of having their students learn about it. They feel like they can have an impact.”

Ranger’s bullfrog project is a great example of that impact, but it isn’t the only one. A fourth-grade teacher who attended a PEI WISC workshop in 2016 sent a letter sharing how the invasive species lessons had affected her class. “My student informed me that her grandmother’s yard was taken over by Himalaya blackberry,” she wrote. “She helped her grandparents remove as many as they could using clippers and bulling. It was a big job, but she said it was worth it.”

“My students have developed empathy for native plants and are currently making a native plant and shrub book from the plants’ perspective,” she continued. “Thank you for your program which has given me resources, expanded my curriculum and has opened more possibilities for my students to become stewards of this great place where we live.”