It had been drizzling throughout the day during The Sailing Foundation’s Youth Sailing Leadership Forum – until, naturally, it was time to go outside for a field experience. Then, it started pouring.

“The participants were mostly sailing instructors,” says PEI’s Northwest FieldSTEM Coordinator Amy Keiper-Gowan, “so their response was, ‘Oh well, looks like we’re going to get wet.” And we did.”

The February 22 event provided resources and networking for instructors of youth sailing programs and K-12 educators. It included practical topics like how to begin the process of starting a 501©(3) along with ideas for enhancing teamwork and fostering youth mental health. Keiper-Gowan’s two sessions gave participants hands-on experiences and resources they could adapt for their sailing programs or classrooms.

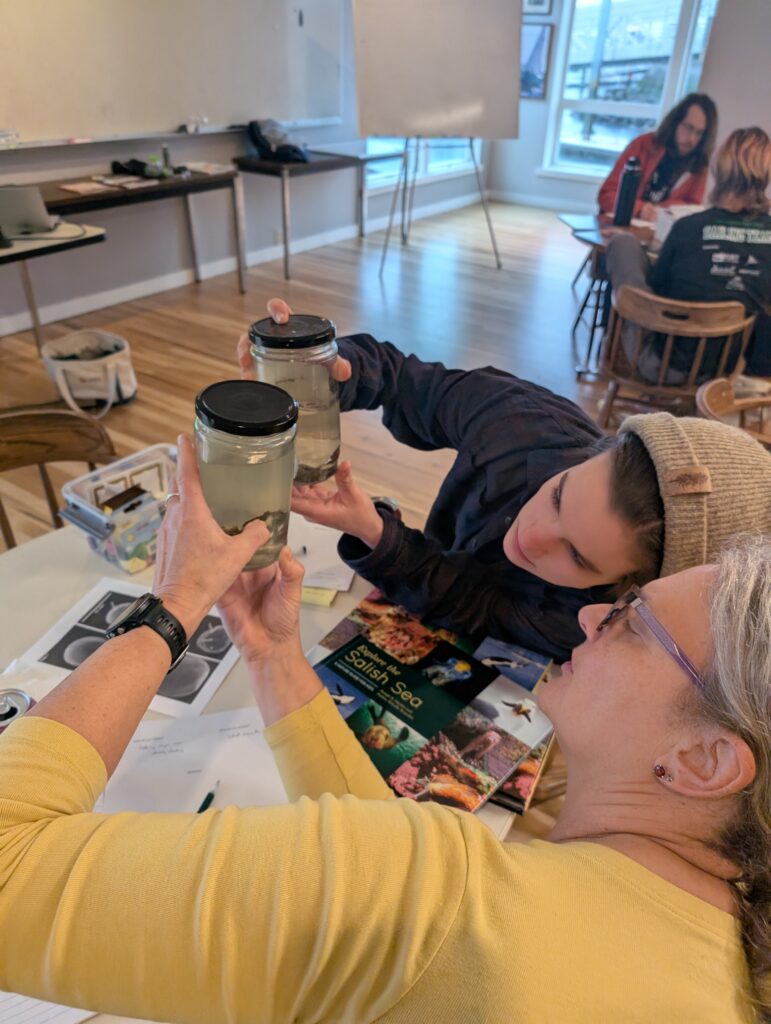

In session one, participants compared oyster shells stored in vinegar to those stored in sea water, checking for misshapenness or discoloration. “The

pictures from Oregon State University showed the misshapen and the healthy larva,” Keiper-Gowan explains. “They noticed bleaching and disintegration on the shells soaked in vinegar, as well as less evidence of life.” Next, they read an Explore the Salish Sea Curriculum (ESSC) chapter about the intertidal zone and what oysters need to thrive within their habitats. Finally, the group speculated on what field investigations they could conduct to gain more information about what was damaging the oyster shells.

“I loved it because it really brought out questions about what impacts wildlife in the Salish Sea,” says Keiper-Gowan. “The adults had a more developed understanding than most students would, but they also experienced that wondering moment and there was a broad range of responses.”

ESSC centers Indigenous ways of knowing alongside Western science, she notes. “When we’re talking about solutions to the impacts of a warming climate on the ocean, we should include Indigenous solutions to the acidity problem. We learned about how the Swinomish Tribe is currently braiding western science monitoring practices with Coast Salish traditional ecological knowledge and engineering design to maintain their traditional clam garden. This garden supports shellfish biodiversity, which in turn increases their ability to filter water while also supporting food security and cultural practices. Students learning two ways of knowing is an important part of this curriculum.”

“It’s always so wonderful, because you develop this sense of community just by going outside. The affective filter just falls away and when you come back, the room feels different. Everybody’s a little more relaxed and our conversations around the data are more authentic.”

– Amy Keiper-Gowan, PEI’s Northwest FieldSTEM Coordinator

Many members of the first group returned for the second session, which is where the rain came in. For their field experience, participants filled a turbidity tube with water and connected probes to measure ocean temperature and nitrate and dissolved oxygen levels. “They kind of took the temperature of the ocean,” says Keiper-Gowan. “I gave them a healthy range of those indicators for the native Pacific oyster, and then they compared their data to that range.” The group also explored the intertidal zone to look for habitat components that would support various types of intertidal life, including oysters. The rain continued relentlessly the entire time.

As often happens, by the time the group returned to the classroom, nature had worked its magic. “It’s always so wonderful, because you develop this sense of community just by going outside,” Keiper-Gowan notes. “The affective filter just falls away and when you come back, the room feels different. Everybody’s a little more relaxed and our conversations around the data are more authentic. People find it easier to bring up their wonderings.”

Keiper-Gowan ended up with a question of her own: why were the ocean’s pH levels different between two points within a short distance of each other? Currently, the average ocean pH level is 8.1, which is what the group measured at the marina in front of their meeting spot. However, at a buoy across the channel, that number was 7.9. Intrigued, Keiper-Gowan contacted Padilla Bay Estuarine Research Reserve’s Executive Director Jude Apple and learned that pH levels vary by time of day and season.

“He showed me a database that we can share with teachers,” she explains. “Because of photosynthesis, the plants in the water remove and store more CO2 in the daytime and summer, making the water less acidic. The data points show that because of respiration and lack of photosynthesis, the ocean is more acidic at night and in the winter. It can change an entire point on the pH scale over the course of a day or several over a year. This highlighted the value of teachers working with science experts in the community during their field investigations project or asking them questions after their field experience. Allowing students to engage on their own and discover their own questions drives the learning and their purpose of connecting with a scientist.”

Participants found the materials and activities relevant for their work, whether as sailing instructors or classroom teachers. “The sailing educators saw direct connections to their program,” says Keiper-Gowan. “A lot of them lead afterschool programs and they talked about how they can modify activities to work with their curriculum. They found the new ideas around teaching marine science really helpful.”